Hanna Sheehy Skeffington

The Sheehy Skeffington name is one which is well known throughout Ireland as being synonymous with feminism and pacifism in the country. However, less known is Hanna Sheehy Skeffington's voyage to the United States in the aftermath of the Rising, where she made the only direct appeal to American President Woodrow Wilson for the self-determination of Ireland. While other influential nationalist figures had long been touring the US attempting to raise support and finances for the Irish cause, none had been successful in gaining an exclusive audience with the American President. Sheehy Skeffington’s feat is made even more impressive considering the meeting took place in a country which had yet to give women the vote!

Breaking The Mould

Hanna Sheehy was born in 1877, in Kanturk Co. Cork. She grew up in a family with deep Republican connections, with her father being imprisoned many times for his republican activities with the Irish Republican Brotherhood. When she was ten, Hanna moved to Dublin along with her family, and later attended St. Mary’s University for Women. At the time, women were not allowed to attend the same lectures as men in UCD or Trinity College, they were however allowed to sit the same exams. This led to Hanna, after graduating from St. Mary’s, obtaining a Masters in French and German from UCD in 1902.

Hanna and Francis

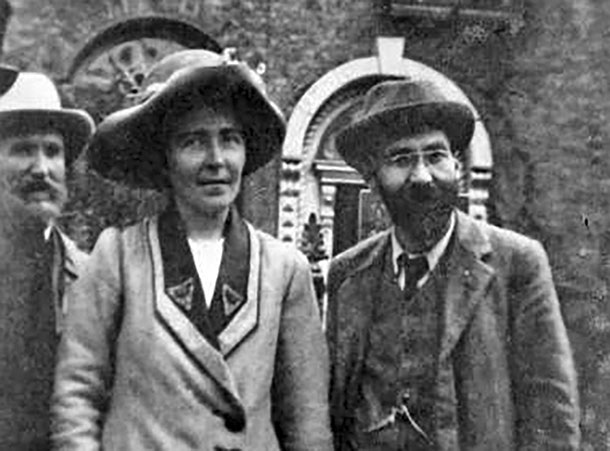

It was during her time as a student in Dublin that Hanna met her future husband, Francis. Francis was hugely active in politics at the time and was a figure who inspired controversy, having a long unkempt beard and proudly displaying a badge that said “Votes for Women”. In 1903, the two got married and in accordance with their strong belief in equality for the sexes, they decided to combine their last names into Sheehy Skeffington.

Hanna was working as a teacher in Eccles Street School, and part time as an examiner. Both her and her husband were involved in branches of the Irish Parliamentary Party and were active in campaigning for Women’s Suffrage across the United Kingdom. In 1908, Hanna became secretary of the Irish Women’s Franchise League. Much of their work was spent petitioning the Irish Parliamentary Party to support the call for women’s enfranchisement, which John Redmond was persistently refusing. Hanna served her first prison sentence in 1912, when she and others in the Irish Women’s Franchise League took direct action and broke windows and fixtures in the GPO, Dublin Castle and the Custom House.

Share the story here and join the conversation!

Caught in a riot

Hanna was a close friend of James Connolly, and was the founder of the Irish Women’s Worker’s Union. During the 1913 Lockout, she ran a soup kitchen which fed many of the strikers. When war broke out in 1914, the Sheehy Skeffington’s began to campaign for peace, calling on pacifist ideals. Francis was sent to jail for his actions, but both continued their campaigns. They had planned to take a holiday for Easter in 1916, but Hanna was warned by Connolly to remain at home.

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington

Despite this warning, she was surprised by the Rising. Hanna’s support here differed from her husband’s views. Despite having a deep opposition to WWI, Hanna supported the rebels in their aims, as they had enshrined women’s rights and enfranchisement in the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. On Monday, Hanna showed her support for the rebel cause by bringing food and supplies to the GPO. Francis however was deeply opposed to the Rising, remaining committed to the pacifist ideals. However, as Hanna was out ferrying messages for the rebels, Francis decided to take action himself. He attempted to organise a militia to stop the looting in Dublin and restore some order to the city. On Monday evening, the two met briefly for dinner before Hanna returned home to their son. Francis stayed out slightly later, and on his way home was arrested and brought to Portobello Barracks. There he, and two journalists, were held without charge by the British Army. On Wednesday morning, all three were shot on the orders of Captain Bowen-Colhurst.

anna was not informed of the murder of her husband, and only found out his fate through the Barrack’s Chaplain. In order to excuse the murder, her family home was ransacked in an attempt to find any incriminating material, but none was found. There was an attempt to cover up the murder, however Officer Francis Vane refused to cooperate with this and launched an investigation. Bowen-Colhurst was deemed insane and sent to Canada for treatment, but an official inquiry only came after Hanna campaigned relentlessly along with the support of John Dillon of the Parliamentary Party. Bowen-Colhurst was deemed guilty but insane and allowed to live out the rest of his years in Canada.

An important Meeting

At the end of 1916, Hanna left for a tour of America along with her son Owen. She had planned to give a speech on her pamphlet “British Militarism As I Have Known It”, which had been banned in the UK and Ireland until the end of the war. However, Hanna didn’t have a passport, which had been refused to her on the grounds of her subversive political views, so she was forced to travel under the alias of Mrs. Eugene Gibbons. Arriving safely in America, Hanna started her tour at Carnegie Hall in New York and continued on to over 250 venues around the country. Her motivation and primary aim of the tour was to publicise the murder and treatment of her husband by the British forces, but also to discuss the wider ideals of the Rising.

Hanna’s tour of America gained attention from numerous sources. She was tailed by the United States Secret Service throughout her time there and British agents were reporting home on her actions. Hanna was also approached to become a member of the Heterodoxy, an extraordinary lunch club which met in Greenwich, New York. The sole requirement of the club was that the individual put forward for membership had stepped outside the normal conventions of the time. Members of the group played a hugely important role in the foundations of American feminism and supported the new wave of female writers. The publicity and official attention that Hanna was attracting in the US allowed her to gain an interview with Woodrow Wilson, the American President in 1917. She encouraged him to support the rights of Ireland to self determination and to urge the British to allow for Irish independence. Wilson’s own views on the Sheehy Skeffington meeting are unclear, but he wasn’t personally against Irish independence. Rather, he saw it as not being immediately important to the ending of the World War, which his country was about to be drawn into.

Hanna was not allowed to return to Ireland legally and was instead forced to travel to England after her tour. She attempted to obtain legal permission to return home, but this was not forthcoming. So in July 1917, she stowed away on a steamship heading for Dublin. Her arrival home did not go unnoticed and within a week she had been arrested. She was held in Bridewell prison for just two days before being sent to Holloway Prison in England, joining other Irish revolutionary’s such as Countess Markievciz and Kathleen Clarke. Once in prison, Hanna went on hunger strike. After two days on hunger strike she was released, under the bizarre system of the Cat and Mouse Act. This allowed for suffragettes on hunger strike to be released when they fell ill and re-imprisoned once they had recovered. However, Hanna escaped being re-imprisoned by returning home to Ireland.

Unfortunate reality

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington and Margaret Pearse, mother of Padraig Pearse

In 1918, Hanna joined Sinn Fein and was asked to stand for election in Dublin. She refused but continued to work closely with the party and with the Irish Women’s Franchise League. She was later elected to Dublin Corporation in 1920 and was subject to constant harassment and raids by the Black and Tans during the War of Independence. In 1922, after the split over the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the outbreak of Civil War, Hanna was asked to return to America by De Valera. She travelled the country attempting to raise money for the anti-treaty side along with Kathleen Boland. In 1926, Sheehy Skeffington joined Fianna Fail on it's formation and continued to focus on Irish Republicanism and Feminism, the two causes which had originally seemed to be moving in tandem.

It soon became clear that both main political parties in Ireland were diverging from the equal society that had been guaranteed for all in 1916. In 1937, Hanna vehemently opposed De Valera’s policies that restricted women’s rights and freedom to work. However, there was no prominent political party that she could join which supported her Feminist views. Her attempts to be elected as an independent candidate during the general election of 1943 failed but she would spend the rest of her life continuing to fight for the rights of the individual, for workers, the republic and of course for feminism. Like many of the revolutionary women, largely failed by the state, Hanna had no pension and was forced to rely on only what she could make herself. She had continued working as a part-time teacher and journalist until, in 1945, she fell ill and had to stop working. Unable to support herself, she never really recovered and a year later, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington died aged 69.

- Written by Daire Collins