Captain Robert Monteith

A Chance Encounter

“Don’t do that!” Three simple words uttered to Robert Monteith that changed his role in the course of Irish history. The words of Tom Clarke seemingly struck a chord with Monteith, who recalls this moment as “the pivot on which I swung towards the greatest and most tragic venture of my life.” From his shop on Parnell Street, Clarke followed this command by stating “I can put you to some other work where men like you will be badly wanted.” Clearly intrigued by the enigmatic nature of Clarke’s words, Monteith deferred his decision to join the Irish Citizen Army. He did not have to wait long to realise why his services were sought. Shortly after their encounter the Irish Volunteers were formed and Robert Monteith’s role was identified as he was elected Captain of ‘A’ Company, 1st Battalion of the Dublin Brigade.

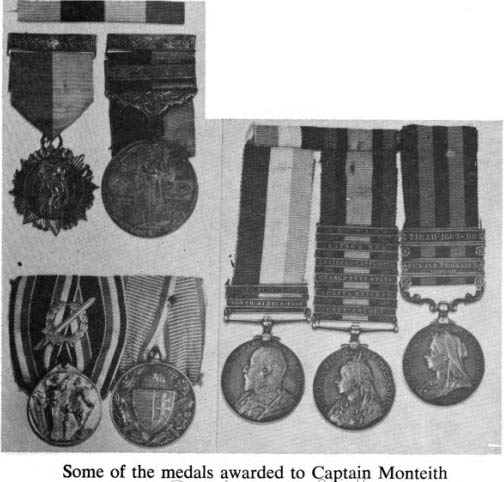

It was no coincidence he was chosen to lead ‘A’ Company, as Monteith had ample experience in military surroundings through his sixteen years of service in the British Army. Having signed up in Dublin in January 1895, asserting that he was 18 when in fact he was only 16, his service would see him reach the furthest corners of the British Empire. He served almost two years training in England with the Royal Horse Artillery, and was stationed in India in October 1896. His three years service in India was spent on the North-West Frontier where he was awarded the India Medal with clasps for the Punjab Frontier 1897/98 and the Tirah Expeditionary Force 1897/98. From here, Monteith was sent to South Africa in January 1900 to partake in the Boer War. His involvement appears to have been widespread as he received battle clasps on his Queen’s South Africa Medal for Tugela Heights in February 1900, the Relief of Ladysmith in March 1900, the Battle of Bergendal, in August 1900 and Laing’s Nek in June 1901. He also received state clasps for service in Cape Colony and the Orange Free State. With the Boer War over, Monteith remained in South Africa until his discharge and return to Dublin in April 1903. The remainder of his years in the British Army were spent in the Reserves in Dublin where he served until finally being discharged in January 1911. By this time, Monteith had married Mollie McEvoy, a widow and mother of three, and had been working for a number of years as a civil servant in an ordnance depot in Dundalk.

British Soldier to Irish Volunteer

So how did a man with such an extensive record with the British Army come to be a part of the revolutionary fervour that was steadily growing in Dublin around 1913? The deaths of James Nolan and John Byrne in late August 1913 were what provoked Monteith into action. Both men died as a result of injuries sustained from members of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and Royal Irish Constabulary during a weekend when the police used excess force to quell the peaceful labour movement in Dublin City. Monteith witnessed first-hand the savagery of the DMP and RIC as they ruthlessly attacked innocent civilians. He recalls one constable, in a patrol of thirty-five men marching along Eden Quay, breaking away to attack a middle-aged man without any sign of provocation. He was then joined by a further two members of the patrol. Monteith howled “You damn cowards” towards them, resulting in a baton striking him across the jaw and shoulder and knocking him to the ground. In a similar, yet more shocking incident, his 14-year-old daughter Florence returned home one afternoon with a blood soaked head after being clubbed by a policeman on North Earl Street. This made the matter even more personal and Monteith was roused into joining the Irish Citizen Army. Instead, his chance encounter with Tom Clarke landed him with the Irish Volunteers and an entirely different destiny was laid before him.

Following his swift rise to become Captain of ‘A’ Company, Monteith became the first to parade his unit through the streets of Dublin city, a time that he recalled with great personal pride. His role in the initial year of the Volunteers was largely focussed around drill instructing. He was recognised as having a particular aptitude for training men, considering his vast experience with the British Army. Indeed, while he was not present on the day of the Howth gun-run in July 1914, it is believed that the drills he was conducting in south Dublin that day were arranged to create a decoy that would lure the majority of the police forces to the opposite end of the city in order to create safer passage to and from Howth. Within days of the crucial gun run, Europe drew closer to a full-scale war which would have dramatic consequences for Monteith.

Deportation Order

“I have done nothing which is illegal or contrary to your laws but in future I will; and for every shilling you have paid me a month I will make the British government pay sovereigns a day. Now you see how England can make rebels. I will square with her this matter.”

- Robert Monteith to Ordnance Depot, Nov 1914

By November 1914, a number of months after the outbreak of World War I, Monteith was approached by the British Army and asked to re-enlist and join the war effort. As a sweetener to the deal they offered him the rank of Major of an Irish unit that would be sent to the Western Front. When this offer was refused they proposed that he travel throughout Ireland and act as a recruiter for the Army. Again, he refused on the basis that he would not betray the men he had been working with for the past year in the Irish Volunteers. On the 12th of November, the day following his meeting with the British Army, Monteith arrived to his job at the Ordnance Depot in Island Bridge to discover he had been sacked without any plausible explanation. Twelve hours later, the reasons became apparent as he received a deportation order in accordance with the Defence of the Realm Act (D.O.R.A.). Two police officers greeted him with the documents at his home in Palmerston Place, Broadstone. Ned Daly sat in the shadows with a loaded pistol in case they had planned any underhanded work. The day after he received his order, he consulted James Connolly for advice at Liberty Hall. Connolly insisted on the finalised edition of the Irish Worker being edited to include the order issued to Monteith, in an effort to highlight the unjust actions of the British. He was of the opinion that Monteith should ignore the deportation order as an act of defiance against the British powers. However, after seeking further consultation from his superiors in the Irish Volunteers it was decided that the best course of action was to adhere to the rules of the order and not risk imprisonment. He was directed to move to Limerick and pick up on his role of drill instructor with the Volunteers there.

Monteith’s activity remained low key for the next number of months. It wasn’t until the day after O’Donovan Rossa’s funeral in August 1915 that Tom Clarke travelled to Limerick to detail Monteith on a very secretive mission. Clarke informed him of the assignment Roger Casement had to assemble a brigade of Irish prisoners of war (POW’s) in Germany. He wanted to send a man with military expertise to command and train the Irish Brigade in Berlin. Monteith did not hesitate to put his name forward for the task. However, Clarke instructed him to sit tight until further notice. Shortly after their meeting, he received the coded message that Clarke was “sending on the books”, meaning he should make preparations to leave for Germany. However, they needed time to carefully plan how to get Monteith out of Ireland and into Germany without arousing suspicion. It was imperative that this assignment remained secret so only a select few within the Irish Volunteers knew about it. A ploy was necessary in order to disguise the true reason for him leaving his Limerick Volunteers and also to deceive the British authorities.

The SS New York

It was arranged that a series of letters would be passed between Monteith and his wife, Mollie, who had remained with her children in Dublin after her husband’s deportation order. They knew their letters were being read by the authorities. In the letters she outlined her financial difficulties and also fears regarding ‘Bob’s’ safety. Similarly, he suggested a sense of weariness and a waning interest in the Volunteers. The letters culminated in a decision to emigrate to the United States, which suited Monteith as the only possible route to Germany would be via the USA. At the same time as this, Bulmer Hobson had issued an order for Monteith to be transferred to Kilkenny. The pieces had fallen into place for him. By indicating his desire to emigrate he would deceive the British into thinking he had given up hope on the Volunteers. On the other hand the order he received to leave for Kilkenny wouldn't give his men in limerick the impression that he was abandoning them. All that remained for Monteith was to receive permission from the Dublin Metropolitan Police to enter Dublin so he could board the boat. On September the 9th 1915, Robert Monteith arrived in New York from Liverpool aboard the SS New York, however less than one month later he would be making a return journey across the Atlantic, with the Irish Brigade and Berlin in his sights.

Stowaway

Monteith’s arrival in New York marked the turning point in his transformation from drill instruction to espionage. After spending a week finding and furnishing a home for his wife and children, he set about finding a ship which would take him to Holland or Norway. Naturally, it was impossible to acquire a passport and attempting to sail as a crew member would have aroused suspicion given that the majority of seamen on these liners were Scandinavian or Dutch. With the help of Clan na Gael and John Devoy, a man called Adler Christensen was selected to accompany Monteith across the Atlantic as a stowaway. Christensen was undoubtedly trustworthy for this dangerous task, given that he had previously accompanied Roger Casement across the Atlantic and through to Germany. The arrangement was for Monteith to meet Christensen at the docks and await his signal to board a ship and then follow him to a secure hiding place. And so, on the 7th October, Monteith successfully boarded the SS United States as a stowaway. The ship was bound for Copenhagen, a journey that would take nearly thirteen days, where Christensen insisted a passport would not be necessary upon disembarkation.

The first few days of his stowaway passed with relative ease, seasickness being the only discomfort he experienced. However, on the eighth night of the journey, news came from Christensen that the liner was to be taken over by a British cruiser and a British crew set aboard. In order to remain undiscovered it was necessary for Monteith to alternate between different cabins as they were searched. With the aid of Christensen, he was able to so without alerting any of the search party. A day later, the ship was brought to port in Kirkwall on the Orkney Islands where the cabin, passengers and mail bags were processed and examined. After a five day detention the British removed five people they suspected to be German agents. Two nights later, on the 20th October, the SS United States arrived at Kristiania (Oslo), where Christensen informed Monteith they would disembark and reach Copenhagen overland, as he had reasons to suspect the ship would be stopped and searched again. Upon preparing to disembark at Kristiania, Christensen brought the alarming news that each passenger would be checked for a passport and necessary documentation. As soon as the ship was brought to port and tied up, armed guards were situated at both ends of the two gangways. In the rush and confusion, Monteith mingled in to the larger of the two crowds leaving the ship, in order to buy some time to conjure a plan to get past the guards. He noticed that while there were two soldiers on each end of the gangway, only the man in the middle was checking papers. As he approached the top of the gangway he stumbled slightly, which gave him an idea. He approached the top of the walkway he began to act drunk and disorderly and staggered into one of the patrolling officers. He continued this with a wild descent down the plank, where the officer checking papers did not dare stand in his way, and just like that Monteith had manoeuvred his way through security and onto land.

After his trickery on the dock, he and Christensen travelled to Christensen’s hometown of Moss, twenty miles outside of Kristiania. Here, Monteith checked in to a Hotel as an American journalist named Jack Murray, and in doing so assured the hotel manager that he had necessary documents and passport. After having breakfast, he decided to take some time to rest but having barely closed his eyes Christensen rushed alarmingly into his room and ordered him to prepare to leave. By mere good fortune, Christensen’s mother happened to be at the local police station when a messenger arrived to report a suspicious stranger at Moss Hotel. Immediately, she made the connection between her son’s unexpected arrival and this stranger. As Monteith took refuge in Christensen’s family home, he learned that only ten days previously a German agent disguised as an American had been arrested and the police and hotel staff were on high alert. By 6:30pm that evening, they had evaded the police and were bound for Copenhagen. The remainder of his journey to Berlin passed without event and at 11:30pm on the 22th October, fifteen days after leaving New York, Monteith arrived at his destination.

Germany & the Irish Brigade

Upon arrival in Berlin, Monteith was greeted with disappointment as he discovered Roger Casement was no longer in the city but had relocated to Munich. Fortunately, he was able to wire Casement to notify him of his arrival in Berlin. The following morning Monteith reported to the German Foreign Office, where his arrival had been eagerly anticipated by Count George von Wedel, the brains of the Foreign Office according to Casement. Von Wedel had arranged passports and relevant identification for Monteith during his stay in Germany. Their conversation largely consisted of the probabilities of the war and also, to Monteith’s pleasant surprise, events in Ireland of which von Wedel was very much aware. Their discussion concluded with a sense of foreboding, however, as von Wedel informed Monteith of Casement’s increasing illness.

After successfully wiring a message to Munich, Casement’s response was a request that Monteith travel south, as he was unfit to travel to Berlin. Reflecting on the moment they finally met one another; Monteith recalled “Feeling, as I did, that I was with one of the outstanding figures in the titanic conflict of arms and brains, it was the proudest moment of my life.” They wasted little time discussing the pressing matters at hand. Casement expected Monteith to be disappointed with the halt in recruitment for the Irish Brigade, which was a result of heavy losses for the Germans at Ypres and the imminent defeat for the German navy, which made the possibility of a minor naval invasion most unlikely. Despite this unpleasant news, his orders from Ireland remained the same and the intention was to push forward with recruitment. After receiving permission to continue recruiting from the War Office in Berlin, both men travelled to Zossen, a town thirty miles outside Berlin, where the men of the Irish Brigade had been stationed in a training camp. Upon arrival, the 14 men lined up to meet their new commanding officer as Monteith made a short speech highlighting the efforts and sacrifices being made in Ireland and the hopes there were for the brigade.

Two days after his first meeting with the Irish Brigade, Monteith was on the road again. This time he ventured west to the prisoner-of-war camp in Limburg an der Lahn to resume recruitment. Alongside him were his Sergeant Major, two Sergeants and an interpreter, Franz Zerhussen. The task of recruitment proved difficult, as Zerhussen recalls in his memoirs that once word began to spread through the camp of the assignment, several of the more experienced Irish POW’s, who were ardently against the idea of the Irish Brigade, were influencing the decisions of the younger men. Nonetheless, Monteith interviewed roughly fifty prisoners a day. With his background in the British Army, he was capable of bringing a level of understanding to each meeting and an insistence that their decision to join the British Army did not make them traitors. He spoke to them on equal ground, soldier to soldier. This was a necessary tactic as there was nothing to offer these men other than the opportunity to fight for Ireland. The majority of the men interviewed appeared to be content with their current situation as prisoners-of-war, and were not inspired by the prospect of fighting for Ireland’s freedom.

NCOs of the Irish Brigade

By November 13th, ten days into the recruitment campaign, Monteith had selected 52 men who were likely to join the Irish Brigade. Problems began to surface as the Germans discovered that his official rank within the Irish Volunteers was just that of a Captain. Major von Baerle was sent to Limburg from the War Office to report on the progress made and in turn attempted to make changes that disrupted Monteith’s routine. Similarly, he did not grant Monteith permission to wear an Irish Brigade uniform when interviewing men. This was considered a massive hindrance, as many of the interviewees questioned the legitimacy of the Irish Brigade. The other major concern for Monteith was Casement’s ever-growing illness. In the diary of his time in Germany, Monteith regularly expressed fear for Casement’s health, mentioning how his fears and disappointments were deteriorating his mental health. By January 1916, little progress had been made on recruitment so Monteith made the decision to return to Zossen where he could drill the 56 men who had volunteered. Over the winter months German officials suggested that the Irish Brigade be sent to the Eastern Front and assist in the invasion of Egypt - by doing so they would be assisting in the independence of another small nation from Britain. Enthusiasm for this proposal was low and only 38 men volunteered. And so, time went on with little or no advancement on the task. Conditions for the Irish Brigade deteriorated to the point where they were viewed as an inconvenience anywhere they went and in some instances, treated as prisoners once again. The frosty reception received by the Monteith and the brigade from the Germans, coupled with Casement’s ill-health created an atmosphere of despondency. To make matters worse, no contact had been made from home in months leaving everyone in a state of uncertainty. However, come early March everything was about to change.

The Long Journey Home

The beginning of March brought a major change in the direction of Monteith’s assignment. Whilst on machine gun practice in Zossen, an urgent message was delivered requesting his presence in Berlin. On arriving at the War Office, it was revealed that a despatch had been received from Irish Revolutionary Headquarters declaring a Rising that would begin on Easter Sunday, the 23rd April 1916. The despatch also made an appeal to the Germans for a shipment of arms, with a submarine escort, to be delivered to Fenit, Co. Kerry on Easter Sunday. Whatever plans the Volunteers had for the Irish Brigade were now set aside and a new mission was at hand. Monteith took charge of planning the operation with the Germans. Their suggestion for transport was a Wilson Liner, weighing 1,200 tons, which they captured from the English at the outbreak of war. It had been transformed and was now disguised as a Norwegian trader ship called the Aud. Monteith believed the necessary numbers of rifles was 100,000, but the Germans insisted the ship could barely take half that amount. The figure offered was 20,000, despite him maintaining that such a number would be insufficient, but argument proved futile as their decision was made.

The new revelations had proven more beneficial than any medicine for Roger Casement, who emerged from his illness with plans for the mission. His initial plan consisted of him and a Sergeant escorting the shipment by submarine, while Monteith would remain in Germany and wait further instruction for arrival with the Irish Brigade. The Germans rejected his proposal on the basis they would not supply a submarine for such a mission. The urgency for a viable plan grew further when Casement received a letter on the 6th of April, via Switzerland, signed ‘A Friend of James Malcolm’; this led him to believe it was a letter from James Plunkett. The letter stated that it was essential that officers were sent with the consignment of arms and that they arrive no later than dawn on Easter Monday. Casement rushed to wire a message back to Switzerland to inform them that no officers would be sent and that a pilot boat needed to be situated north of Inishtooskert Island from the night of Thursday the 20th until Sunday the 23rd, in order to assist the landing of arms. However, shortly after being sent, the message was returned to Berlin and was never delivered to Ireland. The following day, Monteith awaited news from Casement’s meeting with German officials at the War Office. The new instructions were for Monteith, Casement and Sergeant Daniel Bailey (alias Beverley) to travel to Ireland via submarine. News was also brought that the Irish at home were notified of the time and location in which the arms would be delivered. The preparations were made and on the 11th of April they embarked on their journey home aboard the U-20 submarine. However, due to a number of technical errors they forced to stop at Heligoland and transfer to the smaller U-19 just four days after leaving Wilhelmshaven. Five days later, on the 20th of April, they made ready to go ashore in Ireland as Monteith reflected “Thirteen years before, Good Friday, 1903, I landed from South Africa, a soldier of England. On the morrow I was to land – A Soldier of Ireland.”

RIC men recover the dinghy from Banna Strand

As the early hours of Good Friday passed, tension mounted aboard the U-19. As they drew closer to Inishtooskert Island there was no sign of the arranged pilot boat or the two green lights that were to indicate the signal for the boat. Hours went by. News filtered through that the submarine commander could no longer risk losing his ship by remaining in the same location any longer; Monteith, Casement and Bailey were left with no choice but to go ashore in a dinghy. Tension had turned to desolation as the men faced the reality that their mission was most likely doomed. Nevertheless, they needed to make a safe landing ashore and carry out their contingency plan. Attempting to land safely proved more difficult than they envisaged as the waves came thick and fast catapulting each one of them and capsizing their boat. After roughly an hour of arduous work, they just about managed to reach the shores of Banna Strand as the sun rose on Good Friday 1916.

After the failure to locate the pilot boat, the task at hand began to further unravel as they landed at Banna Strand, just outside Tralee. The new plan was to hide Casement in a secure location and for Monteith and Bailey to continue on and locate the commandant of the Tralee Volunteers. Within hours a local farmer, named John McCarthy, had notified the RIC at Ardfert of their landing and Casement was duly arrested. In the meantime, Monteith had established a contact for Austin Stack, commandant of the Tralee Volunteers and declared a matter of urgency that Casement be transported to Dublin for a meeting at Volunteers Headquarters. However, the news soon filtered through of Casement’s arrest and the mission was over.

“Had I known the ending of the chapter, I would surely have let him sleep into eternity in the foaming water on Banna Strand, the water that had tried to be kind to Ireland’s heroes.

A memorial on the spot where Monteith landed in Kerry

And so ended a turbulent chapter for Monteith and indeed for Casement. Monteith spent the next number of months in hiding in various locations throughout Ireland before successfully escaping back to his family in New York in December 1916. His role as an active Volunteer had effectively ended after the events at Banna Strand and he spent the remainder of his years working at various posts throughout America before retiring in 1943 and returning to Ireland for six years. He passed away on the 18th February 1956 but his story has been immortalised through his book Casement’s Last Adventures, where he documents the tales of his time as an Irish Volunteer. Regrettably, the main task for which he is remembered for ultimately ended in failure but there can be no denying the magnitude of his efforts and sacrifices. One thing is for sure - the events of Easter Week 1916 would have been drastically different had his mission succeeded.

-Conor Harte