1916: a captain's table

Artefacts of war of often have unusual stories to tell, if only they could speak. The more often these artefacts, be it maps or weapons, change and cross hands, the deeper the story runs. With a little research and a lot of luck, objects as dull as furniture can provide an immediate tangible link to our shared past.

Chris Shouldice, son of Irish Volunteer Jack, who fought in Reilly's Fort during the 1916 Rising, tells the story of how his father ended up acquiring the Captain's table from the HMY Helga, which shelled Dublin during Easter Week 1916.

What connects the story of German U-Boats, a Fishery and Research vessel, the 1916 Rising and the first Mayo man to win an All-Ireland Senior Football medal? A relatively small mahogany table. While unimposing to the eye, this unremarkable piece of furniture has a long and interesting story to tell. This story begins on the British Naval Ship, the HMY Helga.

This simple, mahogany desk is actual the captain’s table of the Helga, one of the few surviving remnants of a ship with a colourful history. Born out of the Liffey Dockyards in Dublin in 1908, the Helga (originally named the Helga II) began its journey as a Fishery research and protection cruiser. Under the Act of Union, Ireland had control over its own Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction Department, and so the Irish branch of the British civil service used the Helga to its own ends. This remained the case until war broke out, and research ships across the British fleet were transformed into ‘Armed Auxiliary Patrol Yachts’. The Helga experienced this fate in 1915. Her first act of note was to be the one which was etched into Irish history forever. On the night of the 25th of April, 1916, the Helga was ordered up the Liffey and to shell Liberty Hall with her 12 pounder gun.

Share the story here and join the conversation!

Jack Shouldice in his Irish Volunteers uniform.

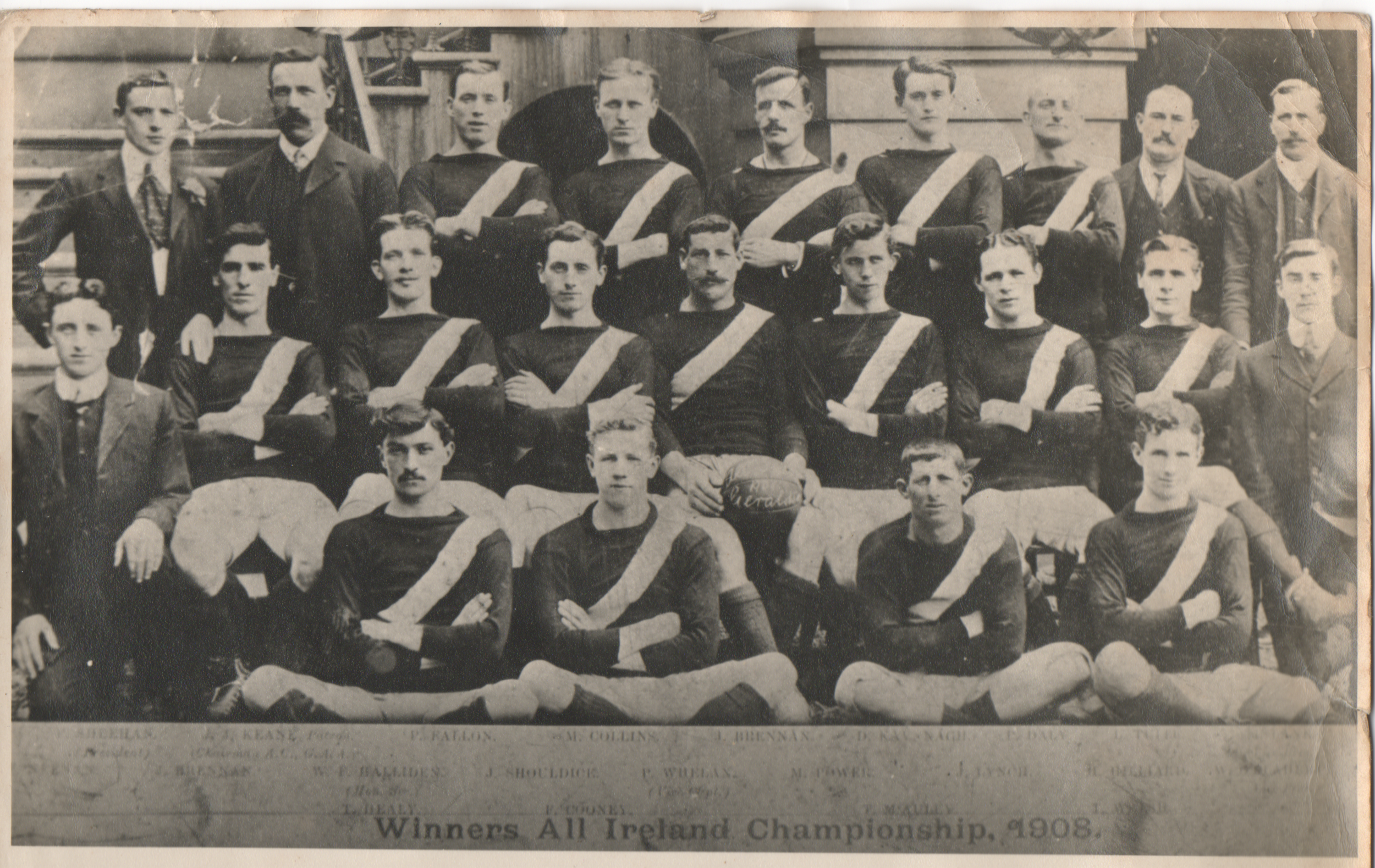

On the opposing side of this shelling, albeit future away up on North King Street, 1st Lieutenant Jack Shouldice of F. Company, 1st Battalion, Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers, was holding the line and returning fire to the British cordon. Jack Shouldice was an interesting man, one who believed truly in the necessity of the Rising but would later eschew all political violence. He left the rural town of Ballaghadereen, Co. Roscommon (but Co. Mayo in GAA terms) in 1899, at age 17 to join the Civil Service in London. It was here, partially due to the anti-Boer sentiments of the British public, that Jack took a more active interest in his Irish political identity. He joined the local GAA club and was initiated into the IRB in 1901 by none other than Sam Maguire. He was an active member of the IRB circle which met at Chancery Lane, under the command of Dr. Anthony McBride, until his transfer to Dublin in 1907. He remained active, bar a brief stint in 1912, when he left due to a political disagreement, but quickly rejoined.

Jack furthered his involvement in the underground politics of Irish nationalism by joining the Irish Volunteers in 1913, where he was elected to the rank of Captain but would eventually have to accept the lower rank of 1st Lieutenant due to his employment as a civil servant. Most of the other high ranking officers were members of the IRB, just like him. It was through these circles that Jack was made privy to the planned insurrection of the Easter Rising. He was tasked with mobilising his company on Easter Sunday and did so with enthusiasm. Despite his dismay at the Countermanding order published by MacNeill in the Sunday Independent, both Jack and his brother Frank came fully prepared on Monday morning. Jack readily took up his commanding post at the crossing of North King Street and Church Street, creating a strong point in the closed Reilly’s premises, which became known as 'Reilly's Fort'. Protecting from above, Frank was positioned with a sniper rifle on the top of the Jameson Malthouse.

As Easter week wore on, the volunteers positions became less stable, numerous times they were pushed back as the British forces attempted to encircle them. Finally, on Saturday the 29th of April, Jack Shouldice surrendered along with the remaining men from his platoon on Upper Church Street. From there they were marched through Parnell Street to the Rotunda Hospital. He was detained in the Richmond Barracks, and was not immediately deported to Frongoch or Stafford detention camp due to his ranking as an officer. Along with this rank came a death sentence handed down by the Field Court-martial of British Commanding Officers. For almost a week, he was held in Kilmainham Gaol woken every morning by the sound of the firing squad executing the leaders of the Rising. On the following Monday or Tuesday, after his surrender and capture, a British officer came to his cell and read out his sentence, he “was sentenced to death but the officer presiding at the court-martial had commuted the sentence to 5 years Penal Servitude.” After a week in Mountjoy, Shouldice served the rest of his time in Dartmoor and Lewes Jails in England until the general amnesty in June 1917.

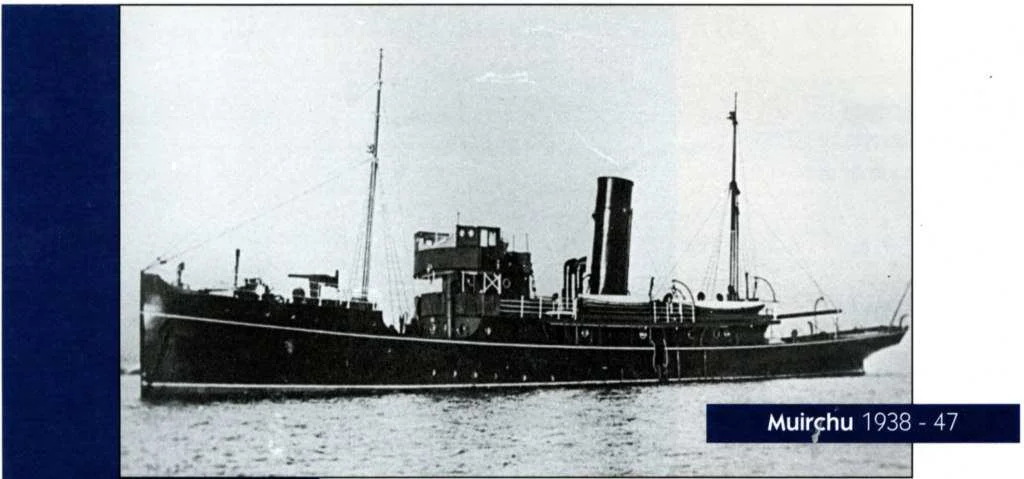

The newly refitted Muirchu circa 1938.

Just as Ireland was moving further away from Britain with every passing day after 1916, the Helga was continuing to perform her duty in the British Navy. In 1918, she successful sank a German U-Boat Submarine off the coast of the Isle of Man. This was the Helga’s first and sole confirmed sinking during the war. However, the presence of U-boats continued to be a real threat to the merchant and passenger vessels in the Irish Sea. In 1917, the Germans began placing their U-boats in the Approaches, the name given to the region near the entrance and exit to the Irish Sea. This was an attempt to stifle the British attempts at Trans-Atlantic trade. The RMS Leinster was typical of their targets, a passenger ship which, along with three other sister ships, made daily crossings from Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) to Holyhead. Known for its exceptional speed, the RMS Leinster held a place of pride in Irish eyes, as it was seen to be their representative in the commercial competition over the Irish Sea. The Leinster along with its sister ships, had won the tender for the Royal Mail delivery from Ireland to the British mainland. While it provided valuable employment to the people of Kingstown and Holyhead in Wales, the requirements of this contract were strict. There was a stipulation that the post collected in Dublin had to be delivered to the mainland the following day. This meant that the RMS Leinster ran daily, and on-time no matter the circumstances.

On the morning of the 9th of October, the RMS Leinster set out from Dun Laoghaire, filled to capacity, for what was to be its final voyage. Despite the U-boat warnings, that morning was no different, the war had been in action for four years, and the crossings were routinely unprotected. Furthermore, the level of censorship which the British government exercised over the press meant that many civilians were largely unaware of the danger that awaited them. Lurking under the waters off Kish Island was U-boat 123, which had already sunk two boats since it left Germany days earlier. At 09:45, the first torpedo was fired, shooting past the brow of the Leinster. The second was a direct hit, and a third torpedo sunk the entire vessel.

Jack Shouldice (Middle Row - 3rd player from left) with the Geraldines GAA team that won the 1908 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship for Dublin.

Coaling, or refuelling, that same morning in Dublin was HMY Helga, the same ship which had been shelling the city two and a half years earlier. That day however, the Helga succeeded in being first on the scene of the Leinster sinking, and managed reach it just in time to rescue approximately 90 passengers, though there is some confusion as to the exact number. These passengers were not returned to Kingstown but disembarked in Wales. Due the controls on wartime press, the British government were keen to keep any such disasters out of the public eye. In fact, one nearby ship was ordered to continue on its route, and not come to the Leinster's aid. A memorial stands today in Dun Laoghaire harbour to the 800 passengers who lost their lives that morning.

After 1922, the Irish Free State was given control of a disarmed Helga for customs patrol and protection of its fishing vessels. Given the terms of the Treaty, the British still maintained the Naval control of Irish waters and there was in effect no Irish Navy. The Irish Coastal and Marine Service was created but quickly disbanded a year later. Rebranded under the name Muirchú, meaning hound of the sea, she was the largest vessel patrolling Irish waters. The Muirchú was re-armed in 1936 and then in 1939, as war in Europe broke out, she was transferred to the Marine and Coast watching Service, where it was joined by other vessels purchased from Britain. Her wartime duties went little further than transporting troops across the River Lee in Cork. As she was being refitted for service during The Emergency, the old fittings were auctioned off.

Chris Shouldice, Jack's son, takes a well deserved break during the filming for 'A Captain's Table'.

At that auction was a Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Civil Servant named Jack Shouldice, the former Irish Volunteer officer who commanded 'Reilly Fort' during Easter week, 1916. Despite his wildly different path, he saw the opportunity to purchase a piece of history, and he successfully bid for the now unwanted Captain’s table of the Helga/Muirchú. This desk was taken to his family home in Fairview where it became the central, but understated piece of furniture in the family study. It was here where Chris Shouldice, Jack’s son, would study throughout his years of education. However, he was unaware of the deep and mixed history that his study desk had seen. He remembers the anger in his father’s voice at the realisation that Chris and his brother had drilled holes in the desk in order to place matchsticks goalposts for push ha'penny games. It was only later, that his father would reveal the historical journey this mahogany desk had taken.

To this day, the Helga’s captain’s desk sits in Chris' wife, Ann's, art studio. Still in active use, the table is covered in scraps of paper and palettes of watercolour paint. There is some irony that the decision to dump the old fittings of the Helga actually saved these insights into history. After the Second World War ended, the Muirchú was released from active service and sold to Hammond & Co ship breaking. However, on what was to be its final journey, the Muirchú went down of its own accord, sinking to the bottom of the sea off the Saltee Islands, rather than submit to the indignity of being broken up for scrap.

- Written by Daire Collins