A Moderate among militants

William X. O"Brien

Militants often take up arms because their political voice is being suppressed, and the only way they feel that they can be heard is through violent means. They aim to create a space where representatives of their cause can debate and effect change in a democratic and peaceful manner. If James Connolly was a militant, William X. O’Brien was his nonviolent counterpart. Allied to the cause, but providing a more moderate viewpoint – one which perhaps wouldn’t be heard if it wasn’t for the attention garnered by the more extreme political activists.

William O’Brien was born in Clonakilty in 1881 and moved to Dublin with his family in 1897. There, he quickly became involved in the Socialist movement and joined James Connolly’s Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP). The ISRP is regarded by many as Ireland’s first socialist party and was one of the first organisations to formally call for a republic. Following in-fighting characteristic of the left-wing movement of the time, the party split in 1904, however O’Brien and Connolly remained good friends and political allies.

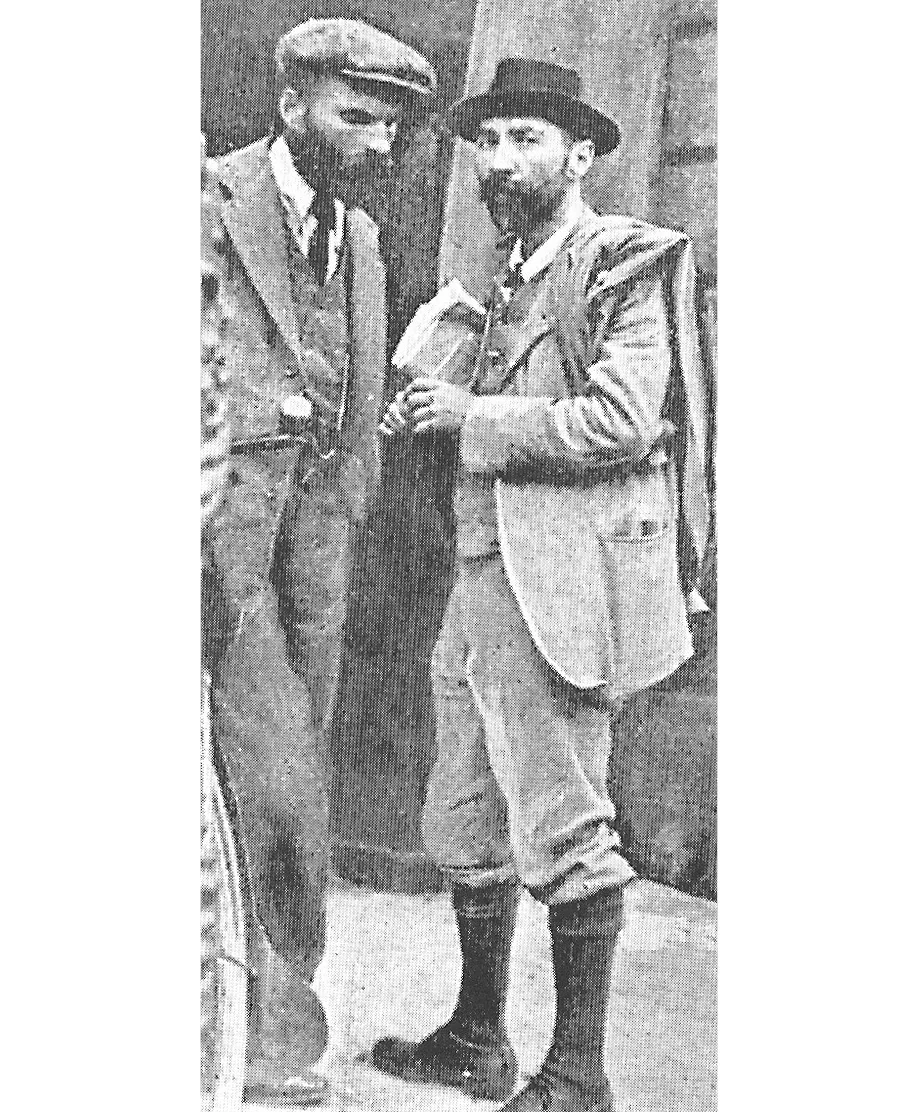

The Irish Trade Union Congress, including (standing): James Connolly, far left; William O'Brien, 2nd left; and James Larkin, 2nd right (seated).

In 1909, James Larkin founded the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) with the help of O’Brien and Connolly. Then, in 1912, the three men became founding members of the Irish Labour Party. The Dublin Lockout in 1913 saw O’Brien take an instrumental role in the union and labour movement. During the Lockout, Connolly formed the Irish Citizen Army, initially as a means of defending workers demonstrations from the police, and later to safeguard their general rights and to promote an Irish Republic. While O’Brien never joined the ICA, he was an extremely valuable witness to the happenings in Ireland from 1913 onwards due to his trusted position within the socialist movement. In a witness statement he wrote for the Bureau of Military History in 1959, he provided a detailed record of the events surrounding the formation of the Citizen Army, the lead up to the Easter Rising, and his involvement in the Rising and its aftermath.

At the outbreak of the First World War, O’Brien became involved in the Irish Neutrality League and the Anti-Conscription Committee, which brought him to the attention of the crown forces and caused him to be interned a number of times by Dublin Castle authorities. This high-level of political activism, during the turbulent years following the 1913 Lockout, led William X. O'Brien to hold an influential and respected position within the socialist movement by 1916. This respected position is illustrated particularly well in one incident – the disappearance of James Connolly.

One day in mid-January of 1916, Connolly left Liberty Hall at lunchtime and was not seen again for several days. It transpired that he had been approached by some members of the Irish Volunteers to discuss a potential insurrection. Connolly had been bemoaning the Volunteer’s apparent indecision on the matter in the Workers Republic newspaper, and had been publicly threatening to stage his own uprising. The Military Council of the IRB, who had been conducting their planning with a greater degree of secrecy, decided they needed to speak to Connolly personally about the matter. For two whole days and nights, he was engaged in an intense discussion with Padraig Pearse and the Military Council about their plans for an insurrection. Meanwhile, his disappearance had set off alarm bells within the Citizen Army leadership. He was presumed kidnapped, and it was feared that he may have even been killed by the British Army.

O’Brien was called in to Liberty Hall to discuss the matter with the leaders of the Citizen Army. There was an understanding between the leadership that if one of them were ever to be arrested, they would start an insurrection regardless. Countess Markievicz was extremely eager to take such drastic measures, and it was only by O’Brien’s intervention that this was prevented. Although he wasn’t a member of the Citizen Army, he argued with Markievicz against such a swift call to arms, and managed to get her to concede to delay any action by 24 hours, following which O’Brien promised he would withdraw from the matter. His perceived closeness with Connolly and respected standing in the labour movement allowed him to exercise such authority in the situation. Mercifully, Connolly turned up the following day, refusing to say where he had been. However, from that point onwards, the attacks on the Volunteers ceased in the Workers Republic, and four months later Connolly’s name appeared on the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

O'Brien (left) and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington

O’Brien’s work for the ITGWU would have meant that he spent a lot of time in the confines of Liberty Hall, and he was there at the start of the Rising on Easter Monday, 1916. Recognising his future potential as both an orator and a political organiser, James Connolly instructed his friend to “go home now and stay there; you can be of no use now but may be of great service later on”. O’Brien returned home as instructed, and heard sporadic reports of the fighting throughout the day from various visitors.

On Tuesday, he decided to investigate the situation himself and went to the GPO. There, he met Connolly and the two conversed at the corner of Henry Street for some time. Connolly reported that the Citizen Army had taken heavy casualties during the fighting at St. Stephen’s Green, having come under intense machine gun fire from the roof of the Shelbourne Hotel. The two friends continued their discussion until a commotion was heard coming from O’Connell Bridge which prompted Connolly to retreat back into the relative safety of the GPO. O'Brien noted in his Bureau of Military History statement that “he made no reference to the general situation, but to me he seemed rather depressed”.

Shortly afterwards, O'Brien encountered Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, who was very concerned about the looting of shops and businesses across Dublin city, and was anxious to take steps to prevent it. O'Brien had however, already raised his concerns on this issue with Connolly, who had dismissed it as “one more problem for the British.” Sheehy-Skeffington informed him then that a British Naval cruiser and two gunboats had arrived in Kingstown Harbour (now Dun Laoghaire). O’Brien returned to the GPO to pass on the information before the pair adjourned to the home of Jennie Wyse-Power for breakfast. It would be the last time that he would see Skeffington alive.

Wednesday and Thursday saw O’Brien trapped in his house on Belvedere Place, near the North Circular Road, as British troops fortified the area and ordered that no doors or windows be opened. A number of houses were searched, including those on either side of O’Brien’s, but fortunately his was not, as he was hiding James Connolly’s 15 year old son Roderick, who had been at the GPO since Easter Monday but was forced to leave as the situation became more dangerous there. O’Brien had initially been hesitant to take him in, as incriminating papers he kept in his house would spell trouble for both of them if searched. It was decided that in the event they were searched, Roderick’s name would be given as Cearney along with the Belfast address of Winifred Cearney, who was in the GPO acting as James Connolly’s secretary.

On Sunday, O’Brien returned to the centre of Dublin to see for himself the condition of the city, taking the young Connolly with him. They weren’t long in town when O’Brien was approached by a British Corporal and arrested as an ‘enemy.’ Roderick Connolly and he were held, along with 38 other men, in the Customs House under confusing and uncomfortable conditions. Anxious to send word home that he had been arrested, but also to remind his family and associates not to enquire for Roderick Connolly by name, he enlisted some passers-by to bring the message ‘Boy Cearney is in Customs House’ to his residence in Belvedere Place.

Richmond Barracks, Inchicore, where O'Brien was detained along with the majority of the rebels in 1916

At one point they were told they were not prisoners at all, and were instead being held for their own safety, with their captors even giving them whiskey. However, a number of attempts were made to interrogate O’Brien by the soldiers, and the cramped conditions meant there was not even room to lie on the floor to rest. The following day, the prisoners were marched to Richmond Barracks in Inchicore, where most of the rebels were being held while they awaited deportation to English prisons. Roderick Connoly was among these, although he was not interned afterwards.

O'Brien was incorrectly held as a Sinn Fein leader and was told by a British Officer that he would be “for a shooting party.” There were several hundred men being held at the barracks, 40 to a room. After a few days, he was transferred to the gymnasium, where he found Thomas McDonagh, Eamonn Ceannt, Major John McBride, and several other prominent rebel leaders. They had been separated from the main body of prisoners and were not allowed to converse amongst each other. One by one, the other men were taken away for court-martial. O’Brien managed to speak to another prisoner, Thomas Foran, General President of the ITGWU, who had passed McBride in the barracks square. He told him that McBride had met his eyes and traced a finger around his heart, indicating that he was to be shot.

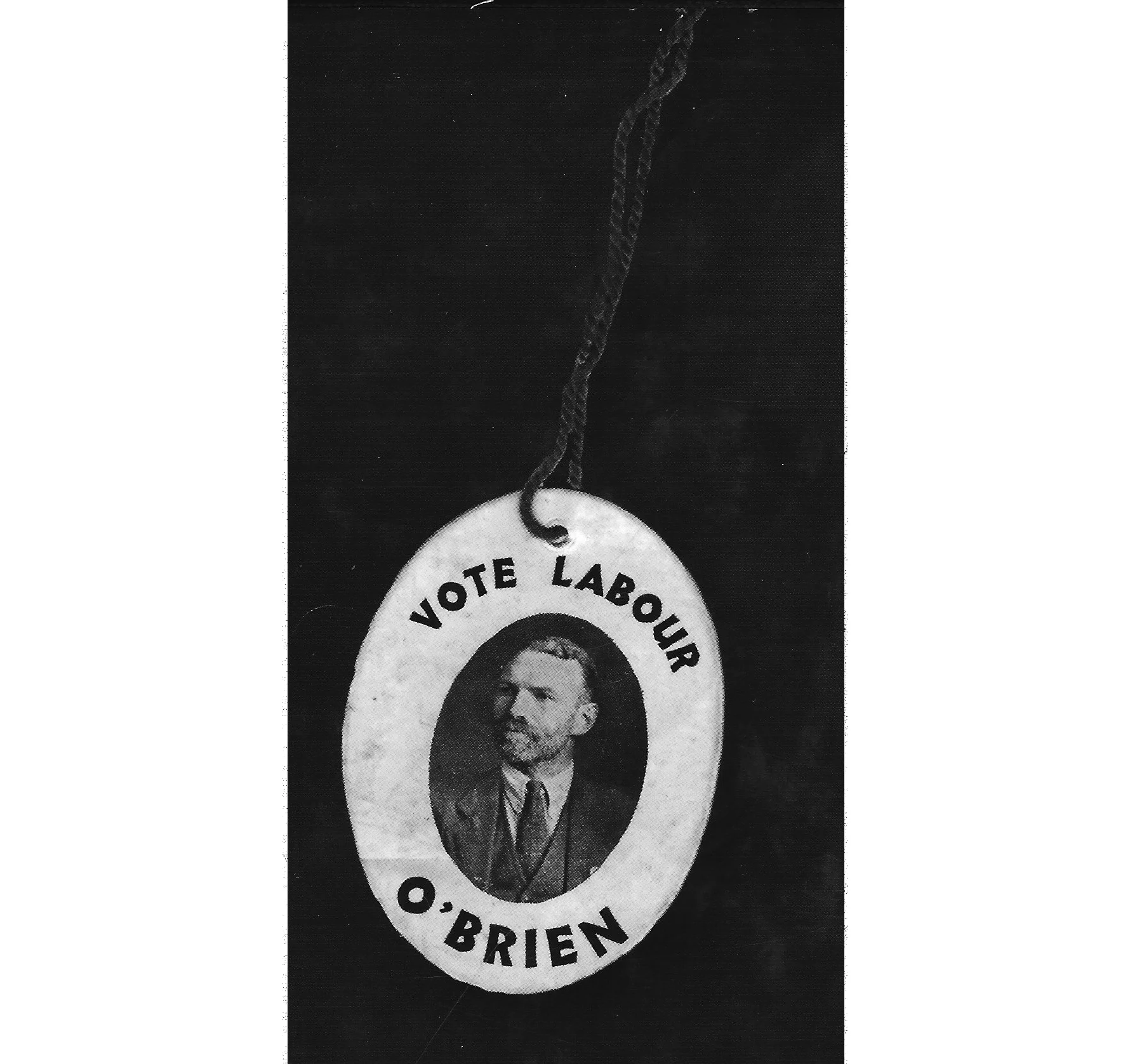

Badge for O'Brien's election campaign

As the days went by, the gymnasium filled up with more rebel prisoners, including Éamonn DeValera. O’Brien recalled that the conditions were very poor, the windows were broken and it became very cold at night. Most men did not have any overcoats and there were no blankets provided to them. After a month of confusion, poor conditions and watching members of the rebel leadership being taken out, never to return, William O’Brien was sent to prison in Knutsford in England. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that despite his innocence, he was extremely lucky not to be executed, given the company he was in while detained at Richmond Barracks. His good friend James Connolly would be one of the final two men to be executed in Kilmainham Jail.

After his deportation, O’Brien experienced the customary tour of British jails and internment camps, during which time he used his experience as a trade union agitator and negotiator to organise the prisoners and complain about the conditions endured by the men. He was released at the end of July, 1916 under the first general amnesty.

O’Brien was now one of the few remaining figures from the early days of the Socialist movement and would go on to hold a considerable influence over the Labour Party and ITGWU. Larkin had departed for America in the aftermath of the Lockout, to raise funds for the movement and recuperate from the strain of the strike. Connolly was dead. He would go on to be elected to the Dail, as a Labour TD, on three occasions, in 1922, 1927 and 1937. O’Brien would continue to remain active in socialist politics well into his 60’s, until his retirement in 1946. He died on October 31st, 1968 at the age of 87.

- Written by Eoin Cody